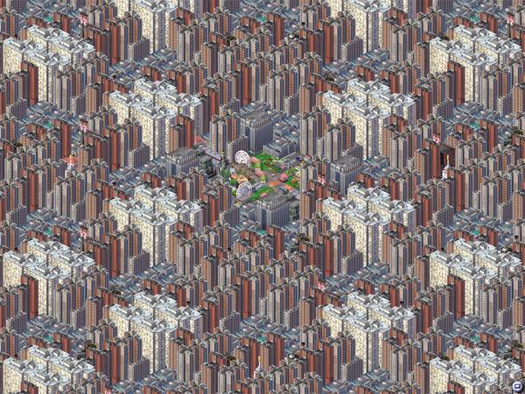

[Screenshot from 'Magnasanti']

Vincent Ocasla’s “Magnasanti” is a SimCity with six million inhabitants, which Ocasla argues represents the maximum possible stable population achievable within the game. A winning solution, he says, to a game without any programmed conditions for winning. Ocasla, a Filipino architecture student, spent four years constructing the SimCity — building the SimCity itself, but also studying the game systems, wading through equations, and working out optimal spatial solutions on graph paper. I was reminded of Magnasanti by Super Colossal’s post on it today, which you should read:

This is the kind of archiporn that I am a sucker for; gamespace urbanism exploited to its extreme condition. Can you ‘win’ urbanism? Is this even urbanism? If not, can we take anything from its construction? The primary move that the city makes is to remove cars altogether and base transport purely on subways. I suspect this is a method to exploit the space otherwise taken up by roads for real estate allowing for an increased population per tile, however, it is a strategy that many cities—Sydney included—are seriously looking into. Remove motor vehicles, increase public transport. Seems like a sound idea. But ultimately, Magnasanti has little to do with urban design and everything to do with gaming systems for maximum reward.

This, of course, is exactly right — the construction strategy for Magnasanti tells us very little about how to construct a city, but a great deal about how to manipulate the internal logic of SimCity (and that is instructive as to the distance between the logic of the city and the logic of SimCity, which results from SimCity being the embodiment of a particular set of assumptions about how cities are planned). Having been reminded, though, I should also link to this interview with Ocasla at Vice. Fascinatingly, Ocasla argues that he constructed Magnasanti as a critique of urban conditions, inspired by Godfrey Reggio’s Koyaanisqatsi. Magnasanti, he says, is not a blueprint for how to build a city. It’s an intentionally hellish vision which exploits the game’s internal logic as commentary:

There are a lot of other problems in the city hidden under the illusion of order and greatness: Suffocating air pollution, high unemployment, no fire stations, schools, or hospitals, a regimented lifestyle – this is the price that these sims pay for living in the city with the highest population. It’s a sick and twisted goal to strive towards. The ironic thing about it is the sims in Magnasanti tolerate it. They don’t rebel, or cause revolutions and social chaos. No one considers challenging the system by physical means since a hyper-efficient police state keeps them in line. They have all been successfully dumbed down, sickened with poor health, enslaved and mind-controlled just enough to keep this system going for thousands of years. 50,000 years to be exact. They are all imprisoned in space and time.

Given mammoth’s professed interest in finding overlap between gameworlds and cities, it’s probably not surprising that this leads me to wonder: what other games might be used to produce critiques of cities, or buildings, or landscapes? I’m particularly interested in this question because of a minor pet theory, which is that one of the most important futures for video games — if they are to become as important a venue for cultural expression as they have the potential to be — is less about the design of spectacularly complex linear (or even branching) narratives for video games, and more about the sharing, re-telling, discussion, and celebration of emergent narratives and objects created by players. Pro Vericelli or Oil Furnace, in other words, not Mass Effect.

A little while ago I spat out a series of tweets for “#idiosyncraticallyarchitecturalvideogames”, some of which (Love, Detonate, Mirror’s Edge) would seem to be excellent fodder for this sort of thing. If, for instance, as Geoff Manaugh has argued, “the bank heist and the prison break together might form the architectural scenario par excellance“, then surely a game like Subversion — “a Mission Impossible-style spy thriller” set within an infinite array of procedurally-generated cities, neighborhoods, buildings, and bank vaults — could be played with the intent of exploring such scenarios (and, if the player is particularly clever, played with the intent of expressing a certain set architectural ideas). What happens, basically, when architects play video games as architects?

[Thanks to Tim Maly for the tip on Subversion.]

"

No hay comentarios.:

Publicar un comentario